Chapter 1. Schooling the New Negro: Progressive Education, Black Modernity, and the Long Harlem Renaissance

by Daniel Perlstein

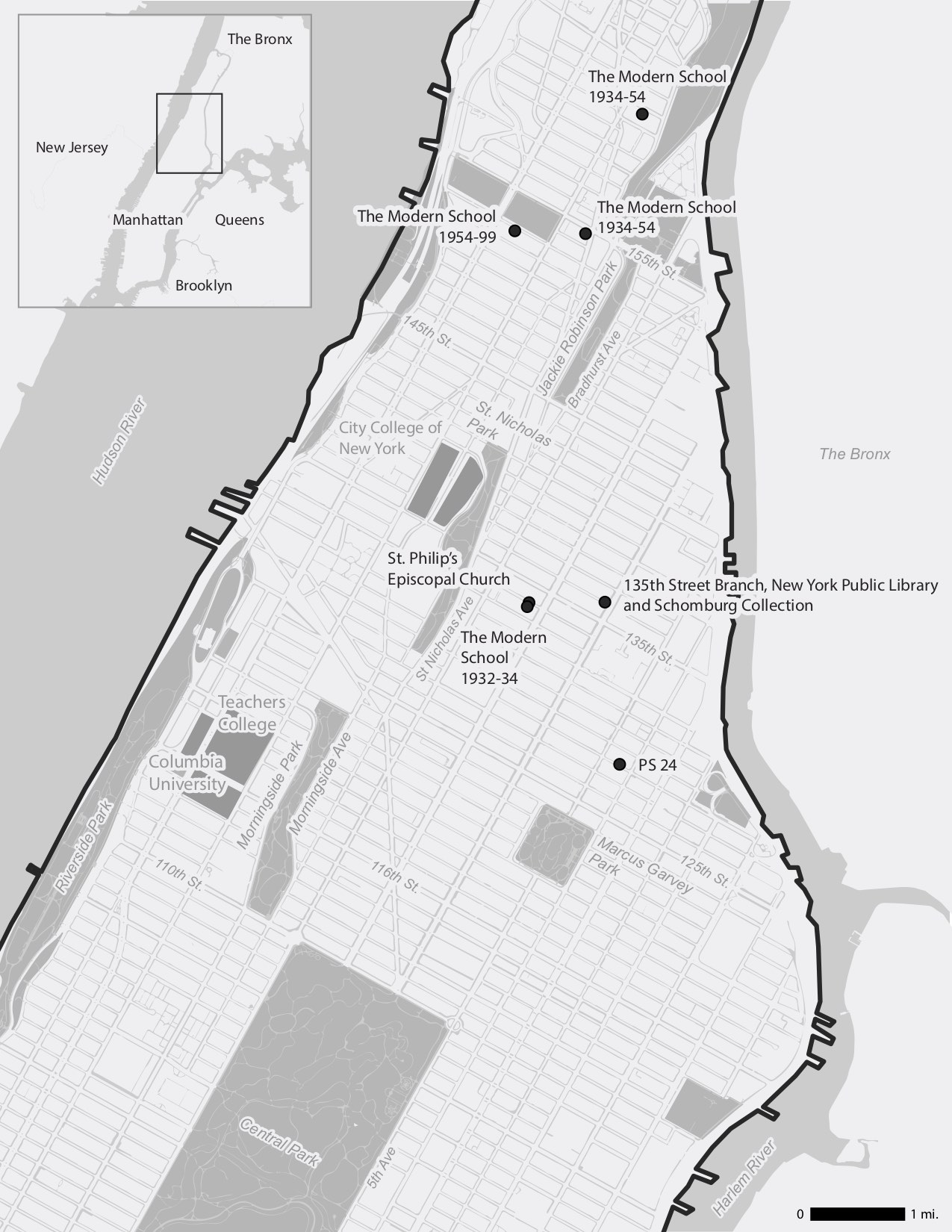

Map design by Rachael Dottle and customized for chapter by Rachel Klepper. Map research by Rachel Klepper. Map layers from: Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Urban Planning, City of New York; Atlas of the city of New York, borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley New York Public Library Map Warper; Manhattan Land book of the City of New York. Desk and Library ed. [1956]; New York Public Library Map Warper; and State of New Jersey GIS. Point locations from: School Directories, New York City Board of Education, New York Amsterdam News via ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and multiple archival sources cited in relevant chapters.

One afternoon in the early 1930s, young Jimmy Baldwin was asked by his mother if his teacher at Harlem’s Public School (PS) 24 was colored or white. “I said she was a little bit colored and a little bit white,” Baldwin would recall years later in a conversation with psychologist Kenneth Clark. “That’s part of the dilemma of being an American Negro; that one is a little bit colored and a little bit white, and not only in physical terms but in the head and in the heart. . . . How precisely are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation?”1

Baldwin’s teacher—Principal Gertrude Ayer—had long been a fixture of Harlem’s leading social, intellectual, and political circles. She contributed a landmark essay on Black women to the celebrated 1925 New Negro anthology that announced the Harlem Renaissance and she was a featured speaker at the 1927 opening of the Schomburg Collection at Harlem’s 135th Street Library. But as Baldwin sensed, Ayer’s understanding of the multiple demands and educational tasks facing African Americans was complex. To enable students to make sense of and navigate that complexity, Ayer, as the Pittsburgh Courier reported, was “a specialist in progressive education.” Her “pupils are encouraged to think [their] own problems out.”2

Not far from Gertrude Ayer’s 128th Street school, another Black Harlem educator was developing a different version of progressive education, but one that was also “a little bit colored and a little bit white.” In 1934, Mildred Johnson opened The Modern School at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church on 134th Street. One cloudy November morning, Johnson discovered a Con Edison worker at the door, there to turn off the power because St. Philip’s had been unable to pay its utility bill. “We [are] going to spend a day like the pioneer children,” Johnson recalled telling her young students. “We talked about the hard times people had before electricity was put into houses. We made up stories and poems about pioneer times . . . [and] ate by candlelight. . . . . We discussed the making of candles and remade one from an old candle we found.”3

The Modern School’s goal, Johnson proclaimed, was “to develop the full child and make him aware of his responsibilities and opportunities in the world around him. . . . Classroom methods are progressive.” John Dewey and other white progressives had long hailed the pioneer homestead as foreshadowing their pedagogical ideal (as well as the exceptional promise of individual autonomy and opportunity in the United States), and pioneer reenactments were a common means of learning by doing in white progressive classrooms. Black students, however, faced the contradictory task of escaping their brutalizing experience and environment as well as constructing meaning out of them; Johnson transmitted to her students an ideology and identity that challenged the pervasive racism of U.S. life. “Every Modern School child,” she promised, “is indoctrinated with the fact that he must be well poised and be capable of doing everything that he is expected to do just a bit better than his competitor. He must understand his background and be proud of his heritage.”4

Two schools, one public and serving Harlem’s poor, one private and serving its elite, both pedagogically progressive, both headed by educators with stronger ties to the Harlem Renaissance/New Negro era of the 1920s than to Harlem’s radical school organizing of the 1930s. By highlighting the educational concerns at the center of the Harlem Renaissance, we can broaden our understanding of the history of race and education and provide an expansive vision of education for children seeking to construct a meaningful life upon what Ralph Ellison called “the horns of the white man’s dilemma.”5 To do so, the chapter situates Gertrude Ayer and Mildred Johnson’s Black progressive educational visions and practice in the New Negro understandings of race, education, and modern life that emerged in Harlem and that were expressed in celebrated literary works that helped define the Harlem Renaissance.

Historical studies of Harlem and the Harlem Renaissance were forged by Gilbert Osofsky, Nathan Huggins, and David Levering Lewis. Huggins argued that in their efforts to articulate a distinctly Black voice and identity, Renaissance writers lacked individual artistry; Lewis portrayed the same artists as insufficiently connected to actual Harlem life; Osofsky suggested that Harlem’s celebrated writers and literary life masked the then emerging Harlem ghetto. This scholarship invited contrasting naively optimistic Renaissance cultural activities with radical organizing to confront ghetto conditions in the 1930s.6

More recent scholarship has viewed the Renaissance more favorably, situating literary production within the broader patterns of Black life and thought (not only within the United States but across the globe), discovering nuanced Renaissance understandings of the intersections of Black with white and of race with class, gender, and sexuality. Scholars such as Houston Baker Jr. and James de Jongh analyze Renaissance Era Black thought in relation to literary modernism.7 George Hutchinson and Ann Douglas reveal Renaissance intellectuals’ engagement with white thinkers such as John Dewey, challenge notions of autonomous Black or white cultures, and demonstrate the interplay of elite, avant-garde literature and popular culture.8 Finally, historians have illuminated Harlem’s emergence as a both real and imagined space, which James de Jongh has called a “landscape and dreamscape,” neither of which can be understood without the other.9

This more recent scholarship, highlighting interracial meaning-making and notions of identity that extend beyond and problematize racial categories, is vast, but virtually none of it examines the Renaissance as an educational phenomenon. Moreover, this scholarship has had little influence on educational history, which has focused far more on the 1930s and grassroots activism than on elite Black intellectual activity and the questions of epistemology and ontology raised by Black modernists. Building on the more recent Renaissance scholarship, this chapter examines the interplay of Black modernism and progressive education in Renaissance thought and schooling.

Education and the New Negro

The New Negro artists, activists, educators, and intellectuals who fashioned the Harlem Renaissance lived in contradiction. They simultaneously echoed and disavowed what the historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham has labeled the “politics of respectability,” as well as vindicationist campaigns to counter allegations of Black inferiority with accounts of Black achievement. They both embraced calls for Black self-direction and highlighted the centrality of interracial activity. They expressed a growing cultural self-confidence even as they accommodated white patrons. They announced a new racial pride even as they challenged racial essentialism.10

In the first decades of the twentieth century, especially in the urban North, Black people increasingly participated in the broad currents of modern U.S. life. The Great Migration from the Jim Crow South to northern cities, the commercialized economy migrants found there, together with Black political, economic, and cultural activity, transformed African American life. Black artists, activists, intellectuals, and educators were well aware of the enduring power of racism in U.S. society (in the North as well as the South) but also of the ways modern life was reshaping African America and allowing African Americans to reshape themselves.11

“I am not a race problem,” Alain Locke wrote to his mother (and implicitly to W. E. B. Du Bois as well) on becoming the first African American Rhodes Scholar. “I am Alain LeRoy Locke.” (Even in the statement of his name, Locke highlighted the new opportunity for Black people to transcend the limitations that had been placed on them and to redefine themselves. The name his parents gave Locke was Arthur. Alain was his invention.)12

In the new world of the mid-1920s, Locke argued, African Americans were for the first time free to express their full humanity, to represent universal human concerns within the particularities of African American life. Whereas previously, Black writers “spoke to others and tried to interpret, they now speak to their own and try to express.” And Locke was not alone in his view. “I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life,” James Weldon Johnson claimed. “My inner life is mine.”13

Although scholars debate the exact contours of the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro movement it epitomized, one can roughly characterize it as the African American strand of modernism. Modernists expressed the consciousness of the individual in a society marked by fragmentation, fluidity, and uncertainty. New Negro modernists, as Daphne Lamothe argues, challenged “representations of African Americans as subhuman” but also commonsense notions of identity, authenticity, and truth. Rather than seeking to re-create the segregated Black communities of the South, they explored Blackness and its instability at “the borders of American interracial and cross-cultural encounters.” They “were modernists,” Lamothe concludes, “because of their willingness to grapple with the uncertainty of knowing and to use this in self-reflection” and the construction of meaning. “Harlem” emerged as Black modernism’s most important locale and as its symbol for African Americans everywhere. It was both a neighborhood and an ideal to be envisioned and realized. In the words of Alain Locke, it “is—or promises at least to be—a race capital.” For the writer Arna Bontemps, it offered a “foretaste of paradise.”14

Renaissance Literature and Progressive Pedagogy

Like the New Negro construction of meaning and identity amid uncertainty and flux, progressive education’s focus on the meaning-making of learners in a changing environment constituted an expression of modernism. Even though white U.S. progressive educators did little to challenge racial inequality in schooling, New Negro educational ideas had much in common with and owed much to the white mainstream of progressive education.

“Rules . . . precedents . . . [and] knowledge received at second hand,” claimed the teacher and future Crisis literary editor Jessie Fauset in a 1912 report on Maria Montessori, “stifle originality and initiative” and “[train] . . . children . . . to abject dependence.” Instead, Fauset suggested, authentic, student-chosen tasks and activities could “liberate the personality of the child.” For Fauset, progressive education, with its attentiveness to the individuality and autonomy of the student, constituted an antiracist pedagogy.15

Still, educating African American children required inoculating them against a brutalizing environment as much as fostering their capacity for meaning-making within it. Whereas white invocations of fluidity risked masking enduring structures of inequality, navigating the contradiction between modernist dreams and oppressive social structures was the topic of Black modernism in education. At the beginning of The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, the novelist and former school principal James Weldon Johnson describes a row of half-buried bottles forming the edge of a garden. “Once,” the novel’s protagonist recounts, “while playing in the sand, I became curious to know whether or not the bottles grew as the flowers did, and I proceeded to find out; the investigation brought me a terrific spanking.” Rather than encouraging the exploration of one’s environment, the experience of Black racial caste, Johnson argued, was “so narrowing that the inner problem of a Negro in America becomes that of not allowing it to choke and suffocate him.”16

The intersection of modernism, race, and progressive education shaped two celebrated novels that both Harlem intellectuals and later critics have considered landmarks in the emergence of the New Negro ethos. Jean Toomer’s Cane and Nella Larsen’s Quicksand both portray a northern, racially mixed Black teacher who travels south to bring modernity to the Black masses and is crushed in the failure to do so.

A transgressive text that mixes novelistic passages with poems and drama and thus assaults the boundaries and identities of segregated literary genres, Cane reaches a climax in “Kabnis,” the story of a Black teacher’s initiation into the gothic Jim Crow South. Oblivious to lurking white violence, Toomer’s protagonist imagines that “they wouldn’t touch a gentleman.” “Nigger’s a nigger down this away, Professor,” Kabnis’s southern Black companions counter. Racial caste trumps cultural capital.17

Kabnis’s antagonist and perhaps the least sympathetic character in Cane is not a white man but rather a Black vindicationist school principal committed to Tuskegee-style training. The purpose of his school, Hanby proclaims, “is to teach our youth to live better, cleaner, more noble lives. To prove to the world that the Negro race can be just like any other race.” The essence of Black teachers’ pedagogy, in Hanby’s eyes, is demonstrating the virtue of hard work while adhering so well to the etiquette of Jim Crow that students internalize it as well.18

In Kabnis’s eyes, the Black masses offer no more resistance to the South’s dehumanizing regime than their Black overseers. “Negroes . . . are content,” he laments. “They farm. They sing. They love. They sleep.” And in the South’s soporific atmosphere, Kabnis also longs to sleep. “No use to read,” he muses. Unable to awaken Blacks from the stupor to which Jim Crow has consigned them, Kabnis is himself subdued and silenced.19

“Kabnis,” Jean Toomer wrote to his white friend and mentor Waldo Frank, “is Me.” Like his character, the author sought a humanity that transcended the confines of the U.S. racial order. Noting that he had as many white ancestors as Black, Toomer passed sometimes as Black, sometimes as white. If, as he told Frank, his family “lived between the two worlds, now dipping into the Negro, now into the white,” racial identities were arbitrary and fluid social constructs. Alignment with any racial identity inevitably betrayed other aspects of one’s self. Individual meaning-making trumped the claims of inherited caste, culture, or community.20

Toomer found little value in his formal education. The Washington, D.C., schooling of his childhood was an “irksome, tedious, and unrewarding . . . mill of classroom recitations.” Whereas Du Bois attributed the shortcomings of Washington’s Black schools to segregation, Toomer argued that they reflected the wider failure of U.S. education. “The system of instruction” assumed that “a child is naturally recalcitrant and hostile to learning” and that schools needed to “constrain and enforce his education by cramming stuff into him and punishing him if he failed or rebelled against swallowing his allotted portion.”21

Toomer’s critique of existing schools and vision of active, individualized learning were indistinguishable from those of many white progressive educators, but he was also conscious of how oppression undermined self-directed meaning-making through explorations of one’s environment. Working in New Jersey’s shipyards, he encountered “doomed men” whose “faculties of speech and feeling and understanding had been paralyzed.” He compared the dockworkers to slaves. “Poverty and privation,” Toomer lamented to the poet and teacher Georgia Douglas Johnson, “dwarf the soul, weaken the body, dull the mind, and prohibit fruitful activity.”22

As Toomer struggled to reconcile his ideas about education, a friend of his grandfather reported an opening at Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute (Sparta A&I), in Georgia. No less than New Jersey dockworkers, Toomer’s students were crushed by oppression. A few months before his arrival in Sparta, one of the most infamous crimes of the Jim Crow era had occurred nearby. Black peons on John Williams’s plantation were beaten daily and locked into bunkhouses at night. On Sundays, Williams ordered them to run through the woods so his hounds could practice hunting down any who tried to escape. Then, in February 1921, concerned about a possible investigation of debt peonage on his plantation, Williams began systematically killing Black workers who could offer testimony against him. And yet, Sparta A&I seemed to condone the murderous system, advertising during Toomer’s time as acting principal that it offered “a thorough training in Vocational Agriculture. . . . The training creates in the boy a love for the farm, therefore it helps to keep the boy on the farm.”23

Toomer tried without success to enable his Sparta students to see beyond the oppressive circumstances that doomed them. In his ancient history lessons on “polytheism and deity evolution,” he wrote his mentor Alain Locke, “I leap, and then look back to see the bewildered expression on my pupils’ faces.” Like his protagonist, Toomer sought to affirm his own identity in bringing modern ideas to the ignorant masses even though he saw no evidence that the masses had the capacity to absorb those ideas.24

Toomer’s quest for self-realization and self-awareness pushed at the limits of race. He insisted that racial identities, whether Black or white, were traps, and he resisted anything that smacked of racial pigeonholing. His poems were “not Negro poems, nor are they Anglo-Saxon or white or English poems,” he explained to James Weldon Johnson. “They are, first, mine. And second, in so far as general race or stock is concerned, they spring from the result of racial blendings here in America which have produced a new race or stock.” This new race, he envisioned, was “neither white nor black nor in-between.”25

Toomer sought in Cane to reconcile the slave past and Jim Crow present with a human future, but, he conceded, “I did not have a means of doing this.” As he explained to the white theater producer Kenneth Macgowan, his protagonist confronted “the beauty and ugliness of Southern life. His energy, dispersed and unchanneled, cannot push him through its crude mass. Hence the mass, with friction and heat and sparks, crushes him.”26

Kabnis’s failure is not due to a particular pedagogical approach but rather to what Toomer saw as the irreconcilability of existing as both Black and human in Jim Crow America. Still, if Cane’s plot centers on Kabnis’s defeat, its form, constructing art out of the raw material of southern Black folk culture and wildly experimental and idiosyncratic in its assault on literary genres, constitutes a testament to individual agency and thus the antithesis of that defeat. In this contradiction, Cane epitomizes a central theme of New Negro art and suggests the utopian, paradoxical project of New Negro education.

Toomer brought his impulse to teach and his thirst for a wholeness that transcended racial categorization to the emerging Harlem Renaissance. Shortly before publication of Cane, Waldo Frank introduced Toomer to his wife, the progressive educator Margaret Naumburg. She in turn introduced him to the Russian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff’s vision of transcending the “waking sleep” in which we live and realizing our full consciousness and potential. “The very deepest centre of my being,” he would recall, “awoke to consciousness.” Toomer offered lessons on Gurdjieff to Renaissance writers such as Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, Dorothy Peterson, and Nella Larsen. Like many Harlem literati, Larsen soon tired of Toomer’s teachings, which she considered an abstruse “pseudo-religion,” but, as the historian George Hutchinson argues, Toomer’s Gurdjieff-inspired exercises in “self-observation with nonidentification” fostered Renaissance dreams of artistic self-expression, stimulating Larsen’s ambition to write and shaping her texts.27

Like Cane, Larsen’s celebrated 1928 novel Quicksand centers on a teacher. Helga Crane teaches at Naxos, a southern school modeled on Tuskegee. Quicksand opens with Helga in her room. Committed to the sensual “sweet pleasure[s]” of modern life, she exults in a cool bath, private leisure time, beautiful things, and a good book. However, the beautiful fabrics in Helga’s room lie beside “her school-teacher paraphernalia of drab books and papers.” Students are forced to wear dull uniforms and learn dull lessons. Whereas her room offers the kind of materials imagined by progressive educators to foster students’ self-actualizing engagement with their environment, Naxos does not. The goal of its “so-called education” is the “suppression of individuality and beauty.” Students and teachers are herded into the chapel to absorb the “insulting remarks” of a bigoted white preacher who commends them for knowing “enough to stay in their places.” For all its talk of race pride, Naxos, Helga concludes, is not “a school” but rather “a sharpened knife, ruthlessly cutting all to a pattern, the white man’s pattern.”28

The child of a white mother and Black father, Helga had suffered an “unloved, unloving, unhappy childhood” among whites. Only when she enrolled in “a school for Negroes” did Helga discover “that because one was dark, one was not necessarily loathsome, and could, therefore, consider oneself without repulsion.” Helga “ardently desired to share in, to be part of” both the community she imagined Naxos to offer and its promise of uplifting the less fortunate. Instead, her individuality, sensual existence, and “zest” for “doing good to [her] fellow men” were “blotted out.”29

To escape the “shame, lies, hypocrisy, cruelty, servility, and snobbishness” of Naxos, Helga flees to Renaissance Harlem. But no less than Naxos schoolmen, Harlem intellectuals “slavish[ly]” imitate whites while simultaneously enforcing the color line. Either a Black or white identity would require Helga to forswear half of her roots. Defeated, she returns south with a hardscrabble preacher and is consumed by an aesthetically, psychologically, and intellectually impoverished existence.30

As with Cane, Helga’s end does not constitute Larsen’s vision. Like Helga, Larsen suggests, life in the United States is fundamentally interracial, challenging any notion of purity and authenticity, whether Black or white. As literary historian George Hutchinson argues, Larsen’s “defiant stance toward the institution of race is not a form of ‘color blindness’ but precisely the opposite; it derives from and enables her genuine appreciation of human differences that reductive ‘race’ thinking brutalizes.”31

As with Toomer, Larsen’s writing drew on experience. Like Helga, Larsen was the child of a white immigrant mother and Black father. She attended a Chicago public high school at which the English curriculum promoted creative writing, individuality, and the dignity of the learner. Still, Larsen and her white half sister were forced to attend separate schools, a rupture no racial uplift could heal. For Larsen, as for Helga (and Jean Toomer), passing, whether as Black or white, constituted self-denial.32

After high school, Larsen attended Fisk. She reveled in the community of Black students, but Larsen had grown up in a milieu that embraced immigrants and organized labor, and Fisk was hostile to both. Promoting the vindicationist politics of respectability, the school left little room for expressions of individuality. When new rules required women students to wear their uniforms and no more than one ring and to be chaperoned on after-dinner walks, Larsen protested, leading to her expulsion. She then completed the nurse-training program at Harlem’s Lincoln Hospital and was hired to head nursing and nurse training at Tuskegee. Tuskegee, however, showed little interest in utilizing Larsen’s skill and training and, like Fisk, great interest in policing her appearance, behavior, and morality.33

Leaving Tuskegee after a year, Larsen returned to New York, became a librarian, began to write and entered Harlem’s literary circles. Among her first publications were pieces for The Brownies’ Book, a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Crisis children’s supplement. In presuming that Black children, no less than whites, possessed curiosity about the world, capacity for self-direction, and desire for aesthetically pleasing experience, The Brownies’ Book drew on wider U.S. notions of childhood and progressive pedagogy. Still, as Du Bois argued, the dominant culture in the United States led “the Negro child” to associate “the good, the great, and the beautiful . . . almost entirely with white people. . . . He unconsciously gets the impression that the Negro has little chance to be good, great, heroic or beautiful.” The Brownies’ Book balanced progressive pedagogy’s vision of self-directed activity with the need to transmit an alternative to the identities that a racist world had assigned Black children.34

Renaissance Teachers, Progressive Education, and Harlem Schools

The preoccupations of New Negro intellectual life echoed across African America, but they resounded most vibrantly in Harlem. New Negroes typically represented Harlem’s racial common ground from the commanding heights of Sugar Hill, where, as Langston Hughes put it, upper-crust “colored families” lived in “nice high-rent-houses with elevators and doormen,” and sent “their babies to private kindergartens and their youngsters to Ethical Culture School.” (The school was known for both its willingness to enroll Blacks and its progressive pedagogy.) It was only when he entered school, James Baldwin would recollect, that he “began to be aware of Sugar Hill, where well-to-do Negroes lived. I began to be aware of it because many of my teachers lived there.” For teachers and others, Sugar Hill crystallized the contradiction between possibilities that seemed to be emerging and the continuing reality of racial caste.35

On Sugar Hill and elsewhere, hundreds of educators made Harlem home; they were at the center of New Negro intellectual life. Harlem Renaissance impresario Alain Locke was an adult-education leader. The son of schoolteachers, he edited the Progressive Education Association’s When Peoples Meet. The novelist and Crisis literary editor Jessie Fauset taught high school in Baltimore, Washington, and New York. The poet Countee Cullen taught junior high school in Harlem. His good friend, the actor, director, and bon vivant Harold Jackman was also a New York City schoolteacher. The award-winning playwright Eulalie Spence taught English and drama at Brooklyn’s Eastern District High School. When not teaching Spanish at Brooklyn’s Bushwick High School, Dorothy Peterson wrote a novel, promoted the Harlem literary journal Fire, and cofounded the Negro Experimental Theatre. Peterson’s Bushwick colleague Willis Huggins headed the Harlem History Club, which trained a number of Black historians.36

Schoolteachers created much of Renaissance Harlem’s intellectual infrastructure. When Jessie Fauset left the Crisis and returned to teaching in 1927, she lived with her sister Helen Lanning, also a teacher, and together they launched one of Harlem’s most celebrated salons. The teacher Alta Douglass played a leading role in a number of civic and artistic groups and, according to the Atlanta Daily World, was “one of Harlem’s most charming hostesses.” W. E. B. Du Bois was the most visible presence when the 1927 Pan-African Congress met in Harlem, but behind the scenes, Layle Lane and other teachers did much of the organizing.37

In part, the number of New Negro luminaries working in schools reflected a job market in which relatively few occupations were open to educated Blacks. “French classes,” Jessie Fauset sighed, “pay better” than writing. But it was not only economic necessity that placed educators at the center of New Negro intellectual life. Harlem was as much an ideal as a neighborhood and, in the words of the sociologist Ira De A. Reid, “not so much the Mecca of the New Negro” as “the maker of the New Negro.” Teaching constituted a way of articulating and fostering new consciousness as befit a new age.38

Gertrude Ayer embodied many facets of this new consciousness. She was a leading light in refined Harlem society, volunteered at the Henry Street Settlement, and organized Black workers. Ayer joined with Alain Locke, James Weldon Johnson, and W. E. B. Du Bois as a featured speaker at the 1925 celebration that announced the Harlem Renaissance. And as principal of PS 24, Ayer was among Harlem’s best-known educators. Adam Clayton Powell’s People’s Voice deemed her “one of the great oaks in New York City’s pedagogical forest,” her school “a model of modernity” designed “to meet present day needs.” Commending Ayer’s commitment to progressive education, the Amsterdam News marveled that “they learn by doing at Harlem’s only experimental school.”39

Ayer brought a varied background to her work. Her father was an Atlanta University- and Harvard University-educated African American doctor, her mother a white English immigrant. Ayer excelled in New York’s public schools, graduating from high school in 1903. She had studied bookkeeping and stenography, but her mother insisted she not work in an office, warning her daughter, “Never trust a white man.” She turned to teaching.40

Her family history convinced Ayer that the injuries of race, and rebellion against them, were bound together with those of class and gender. Just as Ayer’s mother and father had crossed the color line in a transgressive marriage, her mother’s mother, Ayer maintained, “was a lady. She had fallen in love with a carpenter and paid dearly for marrying ‘beneath her class.’” And just as Blacks and whites conspired to maintain the color line, “the ‘lower’ classes in England frown upon such social ‘mistakes’ as do the ‘upper.’”41

Ayer taught until 1911, when she married the prominent Black lawyer Cornelius McDougald (Marcus Garvey was among his clients), and New York’s ban on married women teachers forced her to leave the classroom. She turned her attention from Black children to their mothers, organizing Black women laundry workers with the Women’s Trade Union League. As the New York Urban League’s assistant labor secretary, Ayer documented that although Black women were often far better educated than white women workers, they held the dirtiest, lowest-paying jobs. Women who had trained to be teachers and office workers were left with “their spirits broken and hopes blasted.” Worse, racial discrimination at work intersected with patriarchal relations at home, creating a double bind for working-class Black women. Ayer reiterated the double oppression Black women faced on the job and at home in her landmark 1925 essay, “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation,” but she also claimed that “in Harlem, more than anywhere else, the Negro woman is free from . . . the grosser forms of sex and race subjugation.”42

When New York City ended its ban on married teachers, Ayer rejoined the school system as an administrator. Building on her social welfare work and exemplifying progressive commitments to educating the whole child and connecting school to life, she focused on vocational guidance and school-based social services. “A child cannot learn if he is not physically fit,” she noted. “If he needs glasses, he cannot see and therefore he cannot learn. If he is undernourished, his mind is not alert.”43

For four years, racist school officials blocked Ayer’s ascent to a principalship, despite her high score on the principal’s exam. When she was finally appointed principal of Harlem’s PS 24 in 1935, A. Philip Randolph excoriated a school official who had portrayed Ayer’s achievement as evidence that the American Dream was within the reach of all. “The thing you call ‘Americanism,’” Randolph countered, “is specious, is unsound, and doesn’t warrant the fealty of black America.” Still, the Urban League and the Chicago Defender cited Ayer’s appointment as evidence of the exceptional opportunities New York afforded Black educators. Ayer’s very career epitomized the contradictory mix of possibility and caste that shaped Black modernity and Black progressive education.44

In the 1930s, as Thomas Harbison argues in chapter 2 of this volume, Harlem increasingly condemned vocational schooling as a means of enforcing Black subordination. Although PS 24 offered vocational guidance and mental hygiene, Ayer rejected Tuskegee-style manual training. “The trades do not welcome [Black youth],” she reasoned, “so we cannot concentrate on trade specialization.” Instead, Black children needed an education that countered society’s image of them. “Colored people lack inspiration because they don’t know what their historical background has been,” Ayer argued. “The Negro woman teacher” had “the task of knowing well her race’s history and of finding time to impart it.” Ayer insisted that PS 24 teach the Black student to “realize: 1. That, in fundamentals he is essentially the same as other humans. 2. That, being different in some ways does not mean that he is inferior. 3. That, he has a contribution to make to his group. 4. That, his group has a contribution to make to his nation, and 5. That, he has a part in his nation’s work in the world.”45

Even as Ayer urged direct instruction to counteract society’s image of Blacks, she embraced progressive approaches that affirmed Black children’s full share of humanity. Teachers, she claimed, were “being trained not to want to make children do things they hate to do just because a grown person thinks it is good for them.” She urged Black parents to stop “whipping, slapping and knocking children about” if they did not want them “to be slaves—humble, fearful people.”46

The job of school, Ayer professed, was to “fill the needs the children feel.” PS 24’s Unit Activity Program relied on experiential learning, self-directed projects, democratic classroom living, and field trips into the neighborhood. The curriculum was intended to shift the focus of elementary school teaching from subject matter to the child. Individual abilities, especially in singing and music, were developed. “Habits and skills,” Ayer insisted should be “practiced in situations created and planned by pupils and teachers together to approximate those in real life.” The teacher’s role, Ayer argued, was “guiding pupils in learning” with kindness rather than directing them with force.47

Ayer’s commitment to progressive education reflected not only the particular situation of Black children but also her belief that “there is more in common than in differences between the races. . . . Harlem parents [are] native Americans for the most part, who perhaps more than others cherish the value of dignity for their personality, the value of opportunity for advancement for themselves and their children, and the values inherent in equal protection under the law.”48

If Gertrude Ayer embodied a progressivism aimed at serving impoverished Black workers and children, Mildred Johnson represented progressivism for the Black elite. Born in 1914, Johnson was the daughter of the famed musician J. Rosamond Johnson and the niece of the poet, novelist, and civil rights leader James Weldon Johnson. Mildred was raised amid the Harlem Renaissance elite. Paul Robeson was a family friend; the white Renaissance kingpin Carl Van Vechten and his wife were Uncle Carl and Aunt Fania.49

As a girl, Mildred attended the Ethical Culture School and its affiliated high school, Fieldston. The schools reflected the educational vision of the white progressive religious and political reformer Felix Adler. He sought to ground religion’s ethical precepts in rational thought and actualize them in social action. In 1877, Adler founded the Society of Ethical Culture, and within a year it had established a kindergarten for poor children. The school’s emphasis on rational thought, learning by doing, manual activity, problem solving, and the testing of ideas and values in social action mirrored John Dewey’s educational ideals. As its reputation grew, upper-class Jewish children banned by other private schools enrolled, transforming the school from an institution serving New York’s poor to one serving its elite. Unlike other New York private schools, the Ethical Culture School welcomed (a few) Black students, and many Black intellectuals and activists, Mildred’s parents among them, were attracted to its progressive pedagogy and politics. In 1928, Ethical’s high school division was split from the elementary school, and Fieldston was opened in the posh Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx. Mildred was among its first students.50

Upon graduating from Fieldston, Johnson entered the Ethical Culture School’s Teacher Training Program. After a dozen years as an Ethical/Fieldston student, Mildred was well-versed in and committed to the Teacher Training Program’s progressive approach. For a nursery school course assignment, she imagined a classroom that included a doll corner, blocks, musical instruments, a nature table, paint, clay, and books for individual reading—all the elements needed for children’s self-directed learning of matters interesting to them. In her first student-teaching placement, Mildred wrote a play about the planets and produced it with her third-grade class, combining her own interest in theater with students’ sustained, active, multidisciplinary study of science.51

After her first student-teaching placement at the Ethical Culture School, Johnson needed a second placement at a different school to complete her training. She had demonstrated her teaching ability and shown excellence in subjects ranging from theater, music, and dance to science. Only one thing disqualified her from a second placement. In 1934, no New York progressive private school employed Black teachers and none other than Ethical was willing to allow a Black student teacher to apprentice in its classrooms.52

The twenty-year-old Johnson responded by opening her own school at the church she attended. St. Philips Episcopal was located near the 135th Street library in the heart of Harlem. In creating her curriculum, Johnson drew on her teacher training program, her own schooling, and a home life in which music, theater, and dance were ever present. With the help of one of her Ethical teachers, she adapted the classroom she had imagined for her nursery school course to her church space. With a $100 donation from an Ethical Culture board member, she bought tables, chairs, and playground equipment. “The plan,” she argued, “was not only artistic but it was educationally correct.”53

In September 1934, Johnson’s school opened with eight students, young children of her Harlem society friends. Her goal, Johnson maintained, was to “provide for continuous activity, with stress on pupil self-direction.” “Since it was to be a modern school,” Johnson explained, “we named the school The Modern School of Harlem. The ‘of Harlem’ was soon dropped.” The school’s very name served to announce an orientation recognized by the Amsterdam News as “progressive.” Over the years, enrollment expanded to more than two hundred nursery and elementary school students, and the school moved to a bigger space funded by Mildred’s father. Even when the grades taught at The Modern School fluctuated, however Johnson’s progressive curricular vision remained constant.54

The Modern School’s initial announcement promised “a program which offers to the child opportunities to become identified with life, and so to develop to the fullest extent in body and mind, thereby becoming a healthy, effective and happy member of society.” “There is no clearly drawn line between the subjects in the school program,” Johnson explained. “Our program . . . is flexible and adaptable to the special needs of individual pupils, groups, and to situations as they may arise. For the most part, the classroom teacher builds her curriculum and adapts it to her particular group of children.” Teachers directed science experiments, social studies projects, and conversations about news events or children’s experiences. Boys learned to dance the polka, waltz, and mazurka; girls did ballet. During the period for free play, the children made use of clay, crayons, paper, scissors, paste, and paint. Blocks and “dress up” costumes served as equipment for dramatic play.55

Modern School students, leading Harlem journalist Sara Slack observed, were “educationally pampered” but “carefully trained.” Children worked at their own pace, but academics were intense. Two–year-olds learned to listen to serious poetry and music. Students did research and wrote their own books about subjects of their choosing, encouraging them “to learn to use many sources of information, to gather many opinions, and use varied sources to find and develop a topic.” By age five children were expected to read and write. “If any one of our children have a reading or language difficulty,” Johnson explained, “he’s given private, concentrated training. You can believe me, we have no foolishness here in reading.”56

On weekly field trips, students explored their neighborhood. Much like the acclaimed white progressive educator Lucy Sprague Mitchell, Johnson had students visit stores and streets to observe commerce, trains, and traffic. Trips to the nearby Hudson River offered the George Washington Bridge, tugboats, barges, and a lighthouse. Rather than constituting a break from academics, Modern School field trips allowed students to observe their environment and figure out what they want to learn more about.57

Each year, The Modern School staged one or two original theatrical “festivals”—adaptations from children’s literature or European dance and theater classics that offered “models of beauty” and a dose of happily-ever-after. Johnson prepared detailed outlines, composed songs, often adapted from the original scores, oversaw the creation of costumes and painted sets, and considered which students would be best fitted for which roles. “Children who have a certain potential,” she explained, are “used in that area of the production where they excel. By following this plan no student is forced into an activity that is beyond his ability to perform. And by the same token, those students who have certain abilities are able to express them. . . . Everyone is a participant.” The festivals, Johnson argued, were “the termination for many of the school’s activities such as music, dance, drama, art, social studies and public speaking. . . . The children not only ‘live’ their part in the festival but learn thru research, stories and oral information about the reason for their contribution.”58

Even as Johnson implemented a pedagogy of self-directed student learning similar to that of Ethical Culture and other white progressive schools, she also “indoctrinated” students with a vision of themselves that challenged the dominant ideology of Black inferiority. Johnson took great pride in the fact that her students “educated [white people] who had never seen a group of well-spoken, well-behaved colored children.” In order to ensure that her charges did not resemble poorly behaved (and, implicitly, just plain poor) Black children, she reminded teachers that “children must be taught that quiet is observed in the halls of the school, on the stairway and to a large degree in the streets.” Black history was a regular part of the curriculum; weekly assemblies and annual festivals ended with all singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” the “Negro National Anthem” (Johnson’s father and uncle wrote it). W. E. B. Du Bois admired The Modern School; the civil rights leader Reverend Thomas Kilgore deemed it “way ahead of its time in its approach to education.”59

Active in organizations such as the NAACP, Jack and Jill, the Urban League, the YWCA, and Girl Friends, Johnson balanced racial solidarity and class privilege. Her students, the New York Age reported, were “children of the professional or white collar class.” The Amsterdam News described the school as “exclusive.” At the annual Christmas productions, the paper reported, “women dressed in minks, over chic afternoon dresses.” Students collected Christmas gifts for underprivileged children who lived near the school but did not attend it.60

Many students loved The Modern School, but others, particularly the 10 percent on scholarships, were put off by the vindicationist enforcement of strict behavior and sense of class privilege. The future writer Toni Cade Bambara received encouragement from her fourth-grade teacher who found that the girl “evidences talent in creative writing.” Still, Bambara, who attended The Modern School in the 1940s, described Johnson as “very mean, very yellow, very strict, and very snooty. She would look down at me coming in there with hand-me-down clothes. I didn’t come in a cab like most of the other student[s] . . . [or] talk about going up to Martha’s Vineyard for the weekend.”61

After attending The Modern School in its early years, James C. Hall Jr. went to the Ethical Culture School and Fieldston and had a distinguished career as a university administrator. But his time at The Modern School left Hall more bitter than grateful. “Out of the group of eight” in his class, Hall claimed, “two committed suicide, one is incurably insane, one who was the brightest ended up at Oxford, and one of the loveliest ones became a drug addict and a prostitute. This mortality rate indicates the tremendous pressure that this group of youngsters was under to perform and transcend their culture and circumstances.”62

Still, the relatively privileged status of Johnson and most of her students fostered a commitment to Black excellence that affected even poor students. Leora King was the daughter of a divorced single mother who had not graduated from high school but who insisted that Leora receive an education that made manifest and enhanced the capacity of Black people to excel. Leora transferred to The Modern School for fourth grade. “A lot of the girls were light-skinned and had long, straight hair,” King recalls. “Everybody seemed so rich, and the students were very class conscious. I didn’t know I was poor until I went there.” Still, “there was lot of Black pride. All our teachers were intelligent, educated.” The school and its accomplished teachers and families “gave me confidence in myself, that I could be well-educated, that I could be successful.” The Modern School, she concluded, “was a turning point in my education. [It] made me believe I could fly.”63

The Educational Legacy of the Harlem Renaissance

What the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called “the high hopes that were kindled” by the Harlem Renaissance gave way to material concerns and radical organizing during the Great Depression. But the Renaissance also ran up against the contractions of its own project. As Harlem’s intellectuals struggled “to uphold the American virtues of progressivism, individualism, and self-reliance,” Nathan Huggins observes, they “were obliged by circumstances to be group-conscious and collective. The American Dream of open-ended possibility for the individual was for them another paradox.”64

Still, just as progressivism in schools long outlasted the Progressive Era in U.S. politics, the Harlem Renaissance in education continued long after it had dissipated in literature and popular culture. New Negro educators’ and intellectuals’ hopes of thinking, writing, speaking, and living as full participants in the modern world echoed in what one might call the Long Harlem Renaissance. Although the author Richard Wright embraced the radical 1930s campaign for the material reorganization of society, he also called for “a tremendous struggle among the Negro people for self-expression, self-possession, self-consciousness, individuality, new values, [and] new loyalties.” The militant educational activists Layle Lane, Williana Burroughs, and Ella Baker traced their politics to a capacity to imagine a different world kindled by the Renaissance. Echoing Du Bois and Locke as well as his schoolteachers Countee Cullen and Jessie Fauset, James Baldwin decried the reduction of Black people to group identities or social problems. The “insistence that it is [a human being’s] categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended” was, he argued a “rejection of life.”65

As Alain Locke urged a group of Philadelphia student writers, Black poets needed to create “less a chant for the dead and more a song for the living. Especially for the Negro, I believe in the ‘life to come.’” In conceptualizing African American culture and identity not as inheritances that define the individual but as raw materials to interpret and transform, and in situating that identity and culture with the broadest currents of intellectual and political life, Harlem’s New Negroes envisioned a society in which African Americans could both maintain group pride and be full participants in U.S. life. Even if Renaissance thinkers underestimated racism’s defining power in U.S. society and thus exaggerated the possibilities within it, their ideals fostered an expansive pedagogy. Black progressive educators simultaneously built upon the capacity of Black children to construct their own understanding of the world and instilled a humanity that enduring structures of oppression sought to deny. In their attentiveness to the particularities of Black experience and its universal resonance, Black Renaissance artists, intellectuals, and educators were the authentic pioneers of the educational frontier.66

| Previous: Introduction | Next: Chapter 2 |

-

Kenneth Clark, “A Conversation with James Baldwin,” in Harlem: A Community in Transition, ed. John Henrik Clarke (New York: Citadel, 1964), 124. ↩︎

-

“Rare Library Brought to Harlem,” Amsterdam News, January 19, 1927, 8; “Woman Principal Runs School Like ‘Big City,’” Pittsburgh Courier, February 27, 1937; and Elise McDougald, “The Task of Negro Womanhood,” in The New Negro: An Interpretation, ed. Alain Locke (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1925), 374–76. Baldwin’s teacher initially gained fame using the name of her first husband (McDougald). When she was a principal, she went by that of her second husband (Ayer). Sometimes she used Elise as a first name, and sometimes Gertrude. For the sake of clarity, she is called Gertrude Ayer throughout this chapter. ↩︎

-

[Mildred Johnson], “A Few Incidents from The Modern School,” n.d., 1, Modern School Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library (hereafter Schomburg); (hereafter MSP). ↩︎

-

“A Few Incidents,” 6; [Mildred Johnson], “Our History and Our Aims,” Silver Anniversary of the Modern School, 1959, MSP; “Schools Plan Fall Openings: Three Progressive Groups Are Ready,” Amsterdam Star-News, September 13, 1941, 10; and Daniel Perlstein, “Community and Democracy in American Schools: Arthurdale and the Fate of Progressive Education,” Teachers College Record 97 (1996): 625–50. ↩︎

-

Ralph Ellison, “An American Dilemma: A Review,” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (New York: Random House, 2011), 339. ↩︎

-

Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto: Negro New York, 1890–1930 (New York: Harper and Row, 1966); Nathan Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971); and David Levering Lewis, When Harlem Was in Vogue (New York: Knopf, 1981). ↩︎

-

Houston Baker Jr., Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); and James de Jongh, Vicious Modernism: Black Harlem and the Literary Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). ↩︎

-

George Hutchinson, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995); and Ann Douglas, Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995). ↩︎

-

de Jongh, Vicious Modernism, 24; see also Andrew Fearnley and Daniel Matlin, eds., Race Capital? Harlem as Setting and Symbol (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994), 185–229. ↩︎

-

Daphne Lamothe, Inventing the New Negro: Narrative, Culture, and Ethnography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 80. ↩︎

-

Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001), 389–90. ↩︎

-

Alain Locke, “Negro Youth Speaks,” in Locke, New Negro, 48; and James Weldon Johnson, Negro Americans, What Now? (New York: Viking, 1934), 102. ↩︎

-

Hutchinson, Harlem Renaissance in Black and White; Lamothe, Inventing the New Negro, 1–3. Locke and Bontemps quoted in Daniel Matlin, “Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto Discourse,” in Fearnley and Matlin, Race Capital, 72-73. ↩︎

-

Jessie Fauset, “The Montessori Method: Its Possibilities,” Crisis, July 1912, 136–38. ↩︎

-

James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (Boston: Sherman, French, 1912), 4; and Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Viking, 1933), 89. ↩︎

-

Jean Toomer, Cane (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923), 171. ↩︎

-

Toomer, Cane, 186. ↩︎

-

Toomer, Cane, 81, 159, 164. ↩︎

-

Jean Toomer to Waldo Frank, January 1923, in The Letters of Jean Toomer, 1919–1924, ed. Mark Whalan (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 116; Nellie McKay, “Jean Toomer in His Time: An Introduction,” in Jean Toomer: A Critical Evaluation, ed. Therman O’Daniel (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1988), 3; Jean Toomer to Georgia Douglas Johnson, June 7, 1920, in Letters, 13; Jean Toomer to Waldo Frank, March 24, 1922, in Letters, 31; and W. E. B. Du Bois, Reconstruction in America (New York: Russell and Russell, 1935), 473. ↩︎

-

Darwin Turner, ed., The Wayward and the Seeking: A Collection of Writings by Jean Toomer (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1980), 45–46; and W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Portrait of Carter G. Woodson,” Masses and Mainstream 3 (June 1950): 20. ↩︎

-

Charles Scruggs and Lee VanDemarr, Jean Toomer and the Terrors of American History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 5, 60; Barbara Foley, “Jean Toomer’s Sparta,” American Literature 67 (1995): 771n17; Turner, Wayward, 123; and McKay, Jean Toomer, 44–45. ↩︎

-

Cynthia Kerman and Richard Eldridge, The Lives of Jean Toomer: A Hunger for Wholeness (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), 81; Foley, “Jean Toomer’s Sparta,” 758; Barbara Foley, “‘In the Land of Cotton’: Economics and Violence in Jean Toomer’s Cane,” African American Review 32 (1998): 188–89; Gregory Freeman, Lay This Body Down: The 1921 Murders of Eleven Plantation Slaves (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1999); and Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute, “Give Your Boy a Chance” [Fall 1921], in John Griffin, Biography of American Author Jean Toomer, 1894–1967 (Lewiston, ME: Mellen, 2002), following 198. ↩︎

-

Jean Toomer to Alain Locke, November 8, 1921, in Letters, 27. ↩︎

-

Jean Toomer to James Weldon Johnson, July 11, 1930, in Jean Toomer, A Jean Toomer Reader: Selected Unpublished Writings (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 106. ↩︎

-

Charles Larson, Invisible Darkness: Jean Toomer and Nella Larsen (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993), 34; and Jean Toomer to Kenneth Macgowan, March 15, 1923, in Letters, 141. ↩︎

-

Turner, Wayward, 3, 126; Jon Woodson, To Make a New Race: Gurdjieff, Toomer, and the Harlem Renaissance (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999); and George Hutchinson, In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006), 184. ↩︎

-

Nella Larsen, Quicksand (New York: Knopf, 1928), 4–6, 8–9, 29, 31, 44; and Hutchinson, In Search, 228. ↩︎

-

Larsen, Quicksand, 7, 11, 52, 63. ↩︎

-

Larsen, Quicksand, 18, 184; and Hutchinson, In Search, 28. ↩︎

-

Hutchinson, In Search, 228. ↩︎

-

Hutchinson, In Search, 19, 46–49. ↩︎

-

Hutchinson, In Search, 56, 62–63, 78–79, 92–93, 101–2. ↩︎

-

Nella Larsen, “Three Scandinavian Games,” Brownies’ Book (June 1920): 191; Nella Larsen, “Danish Fun,” Brownies’ Book (July 1920): 219; Katharine Capshaw Smith, Children’s Literature of the Harlem Renaissance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004); and Christina Schaeffer, The Brownies’ Book: Inspiring Racial Pride in African-American Children (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2016), 28. ↩︎

-

Langston Hughes, “Down Under in Harlem,” New Republic, March 27, 1944, 404–5; and James Baldwin, Evidence of Things Not Seen (New York: Henry Holt, 1995), 68. ↩︎

-

Alain Locke, When Peoples Meet: A Study in Race and Culture Contacts (New York: Progressive Education Association, 1942); Carolyn Sylvander, Jessie Redmon Fauset: Black American Writer (Troy, N.Y.: Whitston, 1981), 27–31, 36, 62; Charles Molesworth, And Bid Him Sing: A Biography of Countée Cullen (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 20, 49; Helen Epstein, Joe Papp: An American Life (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 43–44; “Peterson, Dorothy, Randolph,” in Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Cary Wintz and Paul Finkelman, vol. 2 (New York: Routledge, 2004), 965–66; and John Henrik Clarke, “The Influence of Arthur A. Schomburg on My Concept of Africana Studies,” Phylon 49 (1992): 7–8. ↩︎

-

Elise McDougald, “The Schools and the Vocational Life of Negroes,” Opportunity 1 (June 1923): 10; McDougald, “Task of Negro Womanhood,” 374–76; John Howard Johnson, Harlem, the War and Other Addresses (New York: Wendell Malliet, 1942), 150; Thadious Davis, Foreword, in Jessie Fauset, There Is Confusion (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989), xvi; Cheryl Ragar, “The Douglas Legacy,” American Studies 49 (2008): 137–38 “Nine Participate in Panel Discussion,” Amsterdam News, May 18, 1935, 7; “Mrs. Alta S. Douglass, Teacher and Civic Figure,” Afro-American, January 10, 1959, 7; and “Pan-African Congress Holds Fourth Annual Meet in N.Y.,” Chicago Defender, August 27, 1927, 2. ↩︎

-

Marion Starkey, “Jessie Fauset,” Southern Workman, May 1932, 218; and Ira De A. Reid, “Mirrors of Harlem-Investigations and Problems of America’s Largest Colored Community,” Social Forces 5 (1927): 628. ↩︎

-

“With the Sororities,” Amsterdam News, May 16, 1928, 5; Augustus Dill, “Gertrude Ayer is Guest at Banquet,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 13, 1936, 9; Obituary, Mary Elizabeth Johnson, April 22, 1929, Ayer Scrapbook, Gertrude Ayer Papers, Schomburg (hereafter GAP); “Commencement Address Delivered by New York Educator,” Lincoln University 1947, Scrapbook, GAP; Lauri Johnson, “Making Her Community a Better Place to Live,” in Keeping the Promise: Essays on Leadership, Democracy and Education, ed. Dennis Carlson and C. P. Gause (New York: Peter Lang, 2007), 271; “Negro Woman Gets Top Post in School,” New York Times, February 5, 1935; “N. Y. Civic Club Hears Speeches on Negro Gifts,” Afro-American, March 14, 1925, A2; and “At Experimental School,” Amsterdam News, May 21, 1938, 19; and People’s Voice, February 19, 1944, 1. ↩︎

-

Elise McDougald, “The Women of the White Strain,” in Harlem’s Glory: Black Women Writing, 1900–1950, ed. Lorraine Roses and Ruth Randolph (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1996), 419. ↩︎

-

McDougald, “Women of the White Strain,” 411–19. ↩︎

-

E. David Cronon, Black Moses: The Story of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1955), 112; Frank Crosswaith to W. E. B. Du Bois, August 28, 1925, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries; Gertrude Ayer, A New Day for the Colored Woman Worker (New York: Young, 1919), 9–11, 17, 20, 23; and Elise McDougald, “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation,” Survey Graphic 6 (1925): 689. ↩︎

-

McDougald, “Women of the White Strain,” 419; and “Health Ass’n Hold Annual Meeting,” Amsterdam News, February 23, 1927, 3. ↩︎

-

“Mrs. Gertrude Ayer Appointed Principal,” Chicago Defender, February 2, 1935; Nell Occomy, “Mrs. Ayer Pioneers Social Work,” New York News, August 29, 1931; and “Mrs. Gertrude E. Ayer Tendered Testimonial Dinner,” Scrapbook, GAP. ↩︎

-

“Negro Woman Gets Top New York City [Job],” February 5, 1935, Scrapbook; “Rare Library Brought to Harlem,” Amsterdam News, January 19, 1927, 8; Gertrude Ayer, “Notes on My Native Sons,” in Clarke, Harlem, 144; Elise McDougald, “The Negro Woman Teacher and the Negro Student,” Messenger 7 (1923): 770; and Johnson, “Making Her Community a Better Place,” 272. ↩︎

-

Elise Ayer, “Child Training,” February 8, 1930, Ayer Scrapbook, GAP. ↩︎

-

Carol Taylor, “Retiring Harlem Principal Paves Way for Race Mixing,” New York World Telegram, June 11, 1954; Johnson, “Making Her Community a Better Place,” 272; “Pupils Govern Selves,” Amsterdam News, May 9, 1936; Ayer, “Notes on My Native Sons,” 139; New York World Telegram, February 6, 1935; and People’s Voice. ↩︎

-

Ayer, “Notes on My Native Sons,” 139. ↩︎

-

Jennifer Wood, “Johnson, J. Rosamond,” in Harlem Renaissance Lives from the African American National Biography, ed. Henry Louis Gates and Evelyn Higginbotham (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 296–300; and Mildred Johnson Edwards, “A Few Incidents from . . . Mildred Grows Up During the Negro Renaissance,” n.d., 1–2, MSP. ↩︎

-

Robert Beck, “Progressive Education and American Progressivism: Felix Adler,” Teachers College Record 60 (1958): 78–88; Ellen Tarry, Young Jim: The Early Years of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1967), 223; and Mildred Johnson, “Footnotes on the Modern School,” ca. 1979, MSP. ↩︎

-

Mildred Johnson, “The Plan of a Nursery School,” March 13, 1933, MSP; and Johnson, “Lots of Children, or A Story of Mildred,” 9, MSP. ↩︎

-

Johnson, “Lots of Children,” 6; and Mildred Johnson, “About: The Modern School, 1998 Edition,” MSP. ↩︎

-

[Mildred Johnson], “The Modern School Curriculum,” n.d., 10–11, MSP; Johnson, “Lots of Children,” 10; and Johnson, “About: The Modern School.” ↩︎

-

Johnson, “Lots of Children,” 10–11; “[Faculty] Handbook for the Modern School,” n.d., 10, MSP; “Schools Plan Fall Openings: Three Progressive Groups Are Ready,” Amsterdam Star-News, September 13, 1941, 10; [Mildred Johnson], “A Few Incidents,” 3; untitled 1941 report, MSP; and Charles Wolk to National Bank of Pine Bush, August 17, 1954, MSP. ↩︎

-

Untitled 1941 report; Johnson, “Modern School Curriculum,” 1–11; and Class of 1954, “Class History,” MSP. ↩︎

-

Johnson, “About: The Modern School”; and Sara Slack, “The Modern School: A Story of Progress,” Amsterdam News, November 23, 1963, 35. ↩︎

-

Mildred Johnson, “Statement Regarding Out-of-Door Program,” n.d., ca. 1960, 1–2, MSP; Johnson, “Modern School Curriculum,” 2; and Lucy Sprague Mitchell, “Making Young Geographers,” Progressive Education 5 (1928): 217–23. ↩︎

-

Mildred Johnson to Parent, 1955, MSP; Vernon Sinclair, “Modern School Holds Coronation,” Amsterdam News, May 16, 1953, 34, “How T. M. S. Uses the Festival,” n.d.; Mildred Johnson, “Festival: A Play for Children,” March 11, 1935, MSP; and Nora Holt, “’Modern School’ Children in Opera,” Amsterdam News, July 1, 1944, 9A. ↩︎

-

Mildred Johnson, “Mildred Goes to Camp,” 13, MSP; “Handbook for the Modern School,” 9; Mildred Johnson, “A Bit of Magic Mirror” (festival program), June 27, 1942, MSP; Sinclair, “Modern School Holds Coronation;” Johnson, “About: The Modern School”; Thomas Kilgore and Jini Kilgore Ross, A Servants Journey: The Life and Work of Thomas Kilgore (Valley Forge, Penn.: Judson, 1998), 55; and “Chatter and Chimes,” Amsterdam News, October 14, 1939, 1. ↩︎

-

Victoria Horsford, “Mildred Johnson Edwards, Modern School Founder, Passes,” Amsterdam News, September 6, 2007, 41; Bessie Bell, “Women of Merit,” New York Age, March 1, 1947; “Modern School Marks 35 Years,” Amsterdam News, May 23, 1970, 5; “Modern School Play Notes Yule Customs,” Amsterdam News, December 23, 1967, 11; and Mildred Johnson, “Mildred Opens Dunroven,” 13, MSP. ↩︎

-

Toni Cade Bambara, Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays, and Conversations (New York: Knopf, 2009), 213; and Linda Holmes, A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist (Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2014), 12-13. ↩︎

-

John Hall Jr., Oral History interview, 1986–87, in Anne Key Simpson, Hard Trials: The Life and Music of Harry T. Burleigh (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow, 1990), 187; and Betty Granger Reid, “Conversation Piece,” Amsterdam News, May 23, 1970, 5. ↩︎

-

Leora King to author, August 6, 2016. ↩︎

-

E. Franklin Frazier, “Some Effects of the Depression on the Negro in Northern Cities,” Science and Society 2 (1938): 496, 498; and Nathan Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 41, 59 ↩︎

-

Richard Wright, Introduction, in J. Saunders Redding, No Day of Triumph (New York: Harper, 1942), n.p.; Andrew Kersten and Clarence Lang, Reframing Randolph: Labor, Black Freedom, and the Legacies of A. Philip Randolph (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 204; Joanne Grant, Ella Baker: Freedom Bound (New York: John Wiley, 1998), 26, 28; and James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” in Notes of a Native Son (Boston: Beacon, 1984), 23. ↩︎

-

Abby Arthur Johnson, Propaganda and Aesthetics: The Literary Politics of African-American Magazines in the Twentieth Century (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1991), 91. ↩︎